Dow, Syngenta, Bayer, DuPont, BASF….what do these company names connote to you? You probably know them as some the world’s largest producers of chemicals, from glyphosate to alka seltzer. These companies, along with a few others, own hundreds of other smaller companies. As a group, they responsible for the majority of chemicals produced on the planet, chemicals that define how we grow food, manage our health, and run our industries. But did you know these companies also pose one of the greatest risks to biodiversity threatening the worlds food supply?

In addition to producing the herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides that commonly drench fields, these companies are increasingly altering and patenting the species and varieties on which these chemicals are sprayed. The playbook often goes as follows. Take a common variety that has been grown, saved and selected on for thousands of generations. Use modern GM tech to alter a single gene or two among the plant’s tens of thousands. Apply for a utility patent which claims you’ve invented a novel product. Force this product on the world’s farmers who now have no financial choice but to stay on this technological treadmill. Use patent law to prevent other farmers, gardeners, independent breeders and universities from saving, sharing, and selling the seed or using the genetic material to breed new varieties for the public commons. If this sounds evil, it’s because it is. While in many cases patents can be used to incentivize and reward creativity, this phenomenon does the opposite. By locking up more genetic material in the hands of multinational corporations, intellectual property laws are preventing hundreds of thousands of farmers and breeders the opportunity to use this gift of nature, this public technology, to further develop varieties that will be important to the future of our species. We’ve heard from many organic seed companies and university breeders that are feeling the chill. But the problem gets even nuttier. Now, many of these companies are applying for patents over entire traits, like pinkness in tomatoes, long necks in broccoli or even, get this…drought resistance! These are traits often governed by the interaction of hundreds of genes in ways nobody completely understands (let alone created). It remains to be seen how well some of these more egregious patents will actually get approved, or more importantly, hold up in court if the company actually sues for infringement. The issue really hit home for us local organic seed producers when another small local seed company received a letter from one of the companies mentioned above. It was essentially a soft threat, stating that they were in pursuit of patenting several broad, vague plant traits, similar to the ones I just listed. A more formal way of saying: you little pesky seed companies better think twice before carrying any varieties that also have those traits, cause they’re ours! Oof. Unfortunately, this is all going to get a lot worse before it gets better. I think the best way to counter this trend is to decentralize the seed sector so completely, with hundreds of thousands more breeders, seed savers, regional seed companies, seed libraries, etc, that such patents could never be feasibly enforced. I like to think we’re playing a tiny role in this project. |

Category: Seeds

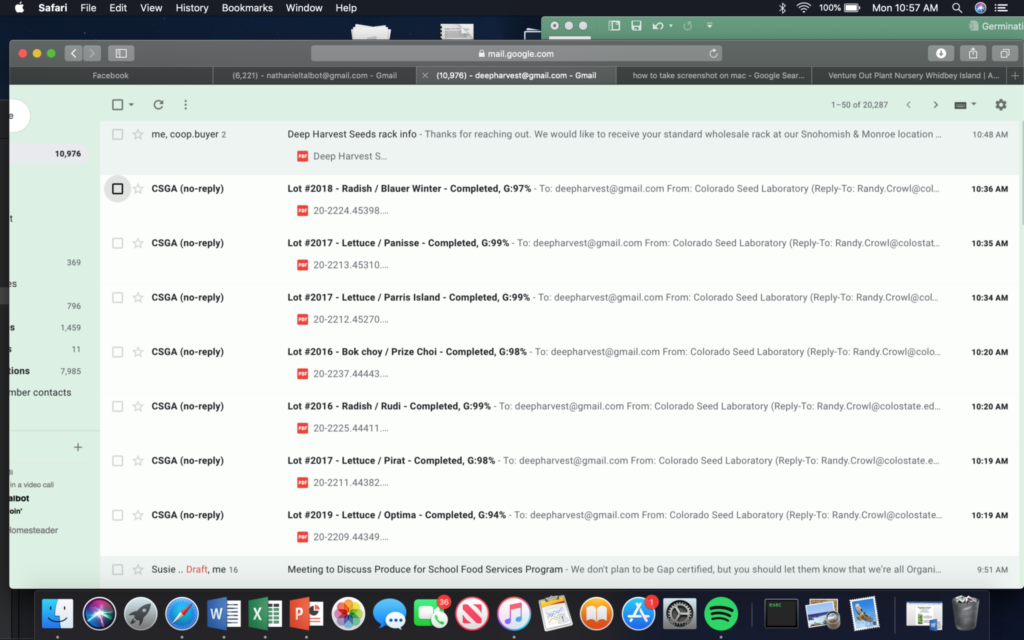

Seed Germination Rates of Deep Harvest Seeds

Not the sexiest title for blog post headline, but we’re going with it. The below photo is an example of what’s been coming into our inbox lately from Colorado Seed Lab. A couple weeks back we sent over 100 samples of seed to the lab for germination testing, and have been getting pretty stellar results, generally between 95-99% viable. While federal standards require seed companies to sell vegetable seeds with between 60-80% germination, depending on the crop, we never sell anything below 80%. 80% tends to be the accepted industry standard, except for certain flowers and herbs which can be hard to get that high. On average, our seed has been tested at 94% viable over the past two years. No bad. It can be a bummer to obsessively tend to a seed crop for 6 months to year and then get a bad germ report back without an explanation for what went wrong. Immature, diseased, dormant? It’s hard to know. There are usually at least a couple duds every year, generally on those heat loving crops that are hard to mature for seed at our latitude and mild climate. Luckily, that hasn’t yet happened yet this sweet germ report season. Crossing fingers the good news keeps a flowin so that we’ll all maximize our chances for vigorous and abundant gardens in 2020.

On-Farm Plant Breeding pt. 2

The seed company is a relatively new type of business, only gaining a foothold in the last 100 years or so with the advents of seed patents and hybrid seed technology. However, back before the seed companies controlled the breeding, production and supply of seeds, farmers were in charge of their own seed stocks. (Well, there was awhile when the federal government and land grant colleges played a crucial role too, but that’s beside the point). Back in the day, farmers had to make sure that they didn’t harvest and sell their entire crop for food, but that they also kept enough plants for saving seed, so that they would have seeds to plant the following season. This process inevitably begs the question: which plants did they sell/eat and which plants did they save for seed? Were the seed plants chosen at random? Did they just save the last few plants that happen to remain in the field toward the end of harvest? Hopefully not. Saving seed gives the farmer the chance to choose the most productive, flavorful, disease-resistant or well-adapted plants to pass on their genes, while culling out all the rest. Thus, most farmers were also de facto plant breeders, actively sculpting the gene pool of their crops toward more productive, resilient futures. Here at Deep Harvest, we are no exception. We’re constantly making choices as to which plants to harvest for CSA, and which to leave for seed saving.

This week planted three different over-wintered root crops for seed: Hilmar Carrot, Touchstone Gold Beet and Tokyo Market Turnip. Most root crops are biennial, meaning that they flower and produce seed their second season of growth after undergoing a winter vernalization period. The roots can either vernalize in the field, or you can harvest them and store them in a damp, cool environment. We chose the latter.

Let’s take beets for example. The first step was to harvest an entire bed of beets and line them all up in a row, over a thousand in total. Then we walked the row and took out the obviously ugly, damaged, or insect-ridden roots. These got tilled into the field. We then evaluate the remaining roots for several preferred traits such as round shape, lack of hairiness, strong tops, dark color, large size and absence of insect damage or disease. We chose the best 200, cut off the stems, and put them into bins surrounded with wood shavings. The rest went to CSA and restaurants. We chose 200 roots because you need at least 80 as a minimum population size to prevent inbreeding depression, and we can assume that many will rot, freeze or get discovered by mice in storage, or perhaps meet other grim fates after replanting next spring. The hope is to have enough survivors to ensure a successful seed crop for harvest in summer 2019. We could have just left them into the ground all winter, but them we’d miss out on the wonderful opportunity for some casual plant breeding. This week the soil warmed enough to replant the roots in rows in the field. Soon they will begin sending out new leaves, followed later by a bolting shoot and flowers. Seed will follow!

On-farm Breeding Projects

By Annie Jesperson

Sorry to get your hopes up, family. Here on the farm, we’re breeding new pepper varieties, not humans. Still a little exciting, perhaps? For us, for sure, but for potential grandmas, likely not so much. While pepper-breeding, like child-rearing, is still subject to the mysterious whims of mother nature, over time us seed growers are direct the evolution of our plants toward the traits we crave.

So what are our goals with pepper breeding? Here in our cool Northwest summers yellow bell peppers can be hard to ripen. The open-pollinated varieties currently on the market have failed to produce mature fruits in our cool, maritime fields. A solvable dilemma? Perhaps! We’re now into year four of de-hybridizing our favorite hybrid yellow bell pepper “Catriona” in order to develop an open-pollinated variety that matures in our region. Additionally, we’re selecting for disease resistance, flavor and yields. We’re getting closer, folks. Stay tuned!

Additionally, we’re working to breed a red bell pepper that is sweet and spicy. Intriguing? For us plant nerds and cooking enthusiasts, indeed! Two years ago, we saved seed on a sweet, red bell pepper called King of the North. At the time, we didn’t realize it had crossed with our spicy Padrone peppers, as we had given them what we thought was ample isolation distance. But, every once in awhile some industrious pollinator carries pollen between varieties that are far apart, even with self-pollinating crops like peppers. Luckily, we sampled our King of the North fruits before selling their seed, and we noted they had a crazy unexpected kick. Ow! That spiciness caught us off guard, but once we bit in to another pepper, expecting this result, we found the experience quite appealing and worth sharing. It’ll likely be a few years before we’ve stabilized this variety enough to warrant selling, but we’re excited for when that day comes and hope you are too!

For now, if you’d like to just grow yourself some nummy peppers, hook yourself up with our spicy Padrones for frying or our sweet Mini Red Bells for salads and stuffing. If you’d like to save your own pepper seed, just grow one variety in a small garden, as peppers need 160 feet of isolation distance to keep a variety pure. For more basic info on how to save seed check out:

https://www.seedsavers.org/

Pacific NW Planting Calendar

We get so many questions from gardeners about the best times for planting different vegetable seeds. The truth is that there is no perfect answer, as the best planting times depend on your soil temperature, microclimate, whether or not you’re using plastic cover or mulch, and when you hope to harvest your produce (to name a few variables). For example, while we advise seeding tomatoes in mid-march or early april, you can plant much earlier if you have a heated greenhouse into which they’ll be transplanted. Also, it’s often best to plant single harvest crops like radishes, head lettuce or carrots several times per growing season, or in many ‘successions.’ Succession planting requires a bit or extra planning, but can result in a prolonged harvest period for you favorite crops. For example we plant beets every three weeks from March through July and arugula every week from March through mid-Sept. During our first several years of growing in the Puget Sound, we consulted the Maritime Northwest Garden Guide for wisdom on the best first and last planting dates for our region. Now, after many years of trial and error, we’ve put together our own Pacific NW Planting Calendar with a more comprehensive crop list and dates that are more specific to the Puget sound. This simple tool will help you identify the window for starting vegetable seeds in your own Northwest garden. Months with an asterisk (*) indicate that it’s best to start seeds indoors during this time for later transplanting outdoors. Click here to download your planting calendar!

Variety Trials 101

Variety Trials 101

Every year, we pick a handful of crops that we want to test in variety trials. What’s a variety trial? Thanks for asking! A variety trial is like a pageant for vegetable or flower varieties, but instead of evaluating for congeniality or swimwear we test for color, vigor, flavor, disease-resistance and other traits a gardener or farmer should care about. If we want to trial, say, red butter lettuces, then we scour every seed catalog (and in some cases more obscure sources of seed like the USDA’s Germplasm Resource Information Network) we can find for red butter lettuces that are open-pollinated (we can’t save seed on the hybrids!). Each variety is then planted out in blocks in the same bed, with enough plants of each variety (usually at least 10, sometimes a lot more) to ensure that we get an accurate evaluation of its genetic makeup. Then, when the crop is mature we gather the farm crew, grab some clipboards and head out for evaluations, which in the case of butter lettuce might be based on flavor, head-density and uniformity, color, and downy mildew resistance. The winner is chosen based on its competitiveness in all, or most of the desired categories. The following season that variety will be planted out in a larger population, not surrounded by other varieties of the same species, for seed saving. This year (2018), we’re trialing six types of dill, six yellow bush beans, eight red leaf lettuces, six different cilantros, five kinds of popcorns, five serrated arugulas, and four varieties of purple sprouting broccolis. It might be an overly ambitious list, but our nerdy biology brains can’t get enough of this stuff! The upshot of all this work is is that our varieties will be more likely succeed on PNW farms and gardens (due to our shared climate, soils and pests) than similar varieties offered by other companies.